HONOLULU — Aina Akamu gave final exams to his students as they sat on bleachers or the floor of the basketball court in the gym in his small town on Hawaii’s Big Island.

He moved his class to the community of Pahala’s gym nearby after he and his students could no longer stand the volcanic ash covering his classroom floor, chairs and desks.

“I decided today I’m not going back to my classroom for the rest of the year,” he said Wednesday, a brief relocation before school ends this week.

Ka’u High and Pahala Elementary School is inundated with gritty, gray ash that has been spewing out of a volcano some 20 miles away. During intermittent explosions at Kilauea’s summit, including one late Thursday, ash shoots high into the sky and drifts down onto the small, rural campus and nearby areas.

No matter how often Akamu sweeps the floors or how many times custodians spray water on buildings, a dusting of ash leaves a normally green tennis court looking gray.

“It keeps blowing around in the wind,” he said. “It’s like we’re fighting a losing battle. We just keep wiping and wiping.”

The ash is a new irritant for a town that’s used to coping with volcanic smog from noxious fumes seeping from the summit and eruption vents. Pahala, near the southern end of the island, is downwind from subdivisions that needed to evacuate after lava started spewing from cracks in the ground three weeks ago.

The smog and ash has led to many absences, Vice Principal Deisha Davis said. One day last week, 48 percent of students were out, she said.

School officials have been monitoring air quality. Students were kept inside Wednesday morning, when sulfur dioxide emissions were high.

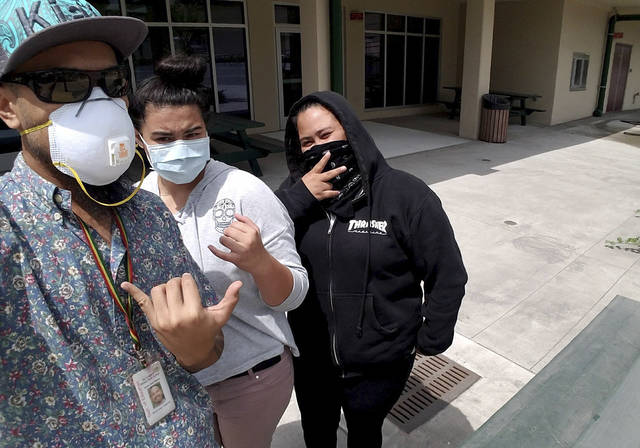

Officials have handed out ash-filtering masks, though they keep running out because some kids misplace them. There’s a “safe room” with air conditioning for students and faculty to go when it’s hard to breathe.

“You walk outside, and you feel like your body is dusty,” Akamu said, likening it to being covered in baby powder. “When wind blows, it gets in your eyes.”

It’s so gritty that when you rub your skin, it leaves small scratches, he said.

Shops in Pahala’s central area have been keeping their front doors closed because of the ash, said Julia Neal, owner of Pahala Plantation Cottages. People take refuge in the air-conditioned bank.

“You see people wearing the masks” in coffee fields, at the store, at the bank, she said.

Residents have been resilient about the ash, she said. Neal’s cottages were filled Friday, when high school graduation will be held in the town’s gym, a focal point of the community.

“Everybody will be there,” Neal said. “Life goes on.”

Another school, Naalehu Elementary, is just 17 miles from Akamu’s campus but it hasn’t seen as much ash, said principal Darlene Javar, who lives in Pahala.

An eruption Thursday night sent an ash cloud about 10,000 feet into the air. Neal said she didn’t notice much more ash after that, likely because the winds had died down.

The National Weather Service said it expects trade winds to slow this weekend, creating hazardous air quality. Volcanic gases, pollution and ash could increase along with sulfur dioxide levels downwind of lava fissures.

Volcanic ash is the reason the area has such rich soil for crops, such as coffee, Akamu said.

“We’re not complaining about the ash. We’re not complaining about Pele,” he said, referring to the Hawaiian volcano goddess.

But he’s hoping his school could get some help cleaning the campus. Some wonder why it hasn’t closed.

“Their staff is cleaning daily. If there was ever an issue with safety, the school would close,” said Lindsay Chambers, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Education. “By staying open and providing that normalcy, the feedback has been that it’s helpful.”